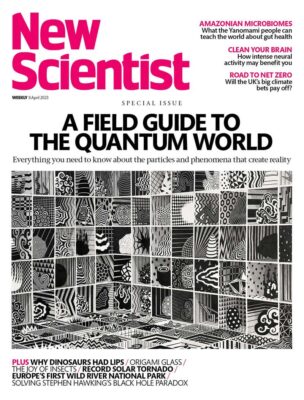

The ancient Greeks speculated that it might be air, fire or water. A century ago, physicists felt sure it was the atom. Today, we believe that the deepest layer of reality is populated by a diverse cast of elementary particles, all governed by quantum theory.

From this invisible, infinitesimal realm, everything we see and experience emerges. It is a world full of wonder, yet it can be mystifying in its weirdness. Over the next 10 pages, Jon Cartwright presents a guide to its inhabitants and their strange behaviours – as well as some of the hypothetical particles that physicists still hope to discover.

We start with what we pretty much know for sure. Visible matter consists of atoms, and at the centre of atoms are protons and neutrons. But even these aren’t elementary particles, as detailed by the current “standard model” of particle physics, our leading description of reality on the tiniest scales. So we begin, deep down, with what matter is really made of.

ELECTRONS

Weighing in around 1800 times lighter than protons or neutrons, electrons add very little to the overall mass of atoms. Without the electron, however, we would scarcely be able to feel matter at all. That is because electrons have a negative charge and exist in an “orbit”, or cloud, surrounding atomic nuclei. When you touch something, the atoms in your fingertip aren’t directly butting up against the ones in an object. Instead, what you are feeling is the mutual repulsion between the negative electrons surrounding the atomic nuclei in your finger and those in the object, via the force of electromagnetism (see “Photons: Electromagnetism”).

The electron plays the lead role in almost all other aspects of everyday life, too. By and large, when atoms bind in solids, liquids and gases, it is through the transfer or sharing of electrons, to balance charge and make things stable. All chemical reactions – from photosynthesis to combustion, from decomposition to the subtle reactions involved in our sense of taste and smell – similarly boil down to electron rearrangement. They are also the vehicles of electricity: their fine manipulation in transistors, which control the flow of electrical current, is what makes computers and many other modern technologies possible. […]

To read the rest of this article, please click here.