Published in New Scientist, 15 Jul 2009

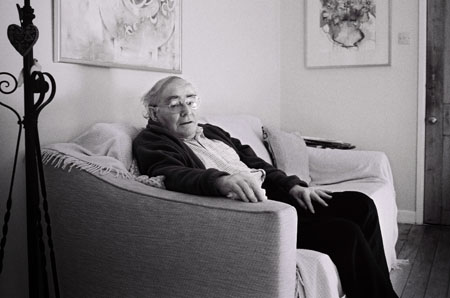

For most researchers, any mention of cold fusion brings back memories of a shameful period in modern science. Now, 20 years after Martin Fleischmann instigated this field, he tells Jon Cartwright that he could not have done anything differently, and that if we cannot get fusion of some sort to work on a large scale soon, we’re doomed

Martin Fleischmann can still remember the morning he entered his lab and saw the terrific hole in the workbench. It was about the size of a dinner plate. Beneath, nestled in a shallow crater in the concrete floor, were the remains of a chemistry experiment that had been fizzing idly for several months without incident. “It had obliterated itself!” he recalls.

It happened overnight, so no one witnessed the meltdown that took place in a basement lab at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, in 1985. But for Fleischmann and his longtime colleague Stanley Pons, there could be only one cause: room-temperature or “cold” fusion. If they were right, the chemists had made a reaction that nuclear physicists had thought next to impossible, one that potentially held the key to almost limitless clean energy. Yet four years later, and just weeks after they had announced their discovery at a now infamous press conference on 23 March 1989, their work was dismissed from mainstream science. Cold fusion became a pariah field, and Fleischmann and Pons fell under the shadow of disrepute. […]

The rest of this article is available here.